If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller

by Italo Calvino

Let’s play a writing and reading game. I’ll write, says Calvino. You read. We’ll check in with each other from time to time to see how it’s going. While I, Calvino, ask you to observe the rules in every paragraph, it is freely acknowledged this game is a set up: if You read If on a winter’s night a traveller please note that You are both the novel’s Reader and its main character. Yes You, dear Reader, are the personaggio through whom our story progresses by turn of page and twist of plot.

It is an intriguing game Calvino plays with us, and especially with You who compasses the novel’s lines with determination and doubt. You have the gleeful and perplexing task of mustering sense and senses from diverting encounters (or chapters if You will) in this engrossing 254-page novel of detours. Calvino wins the race as do You, dear Reader.

Calvino explains who You are in the middle of the novel, once again inflecting the rules by drawing attention to himself as author, and to You as Reader and as Protagonist. ‘This book,’ Calvino writes (p.137),

so far has been careful to leave open to the Reader who is reading the possibility of identifying himself with the Reader who is read: this is why he was not given a name, which would automatically have made him the equivalent of a Third Person, of a character… and so he has been kept a pronoun, in the abstract condition of pronouns, suitable for any attribute and any action.

That’s why You, dear Reader and Protagonist, are both ready and unready for anything in this novel. Despite knowing nothing as Protagonist, as a well-practiced Reader you adeptly shift the shapes in this peculiar game, enabling Calvino to perform his vital understandings of how stories work, and how to write stories. He delights in sharing this know-how which strikes me as remarkable in two ways. First, he calls very direct attention to how the writing works on You, the Reader, passage by revealing passage. Second, he reveals, gleefully and fluently, an uncanny ability to write in diverse genres. Reflecting in these genre mirrors, one after the other in one novel, illuminates for me how similar the genres are in purpose, though different in design.

If on a winter’s night a traveller offers us the first chapters of ten different novels, written in genres ranging from Arabian nights folk tales to a courtly love story translated from Japanese. Let me pluck two sentences (p.219) in magic realism mode to illustrate:

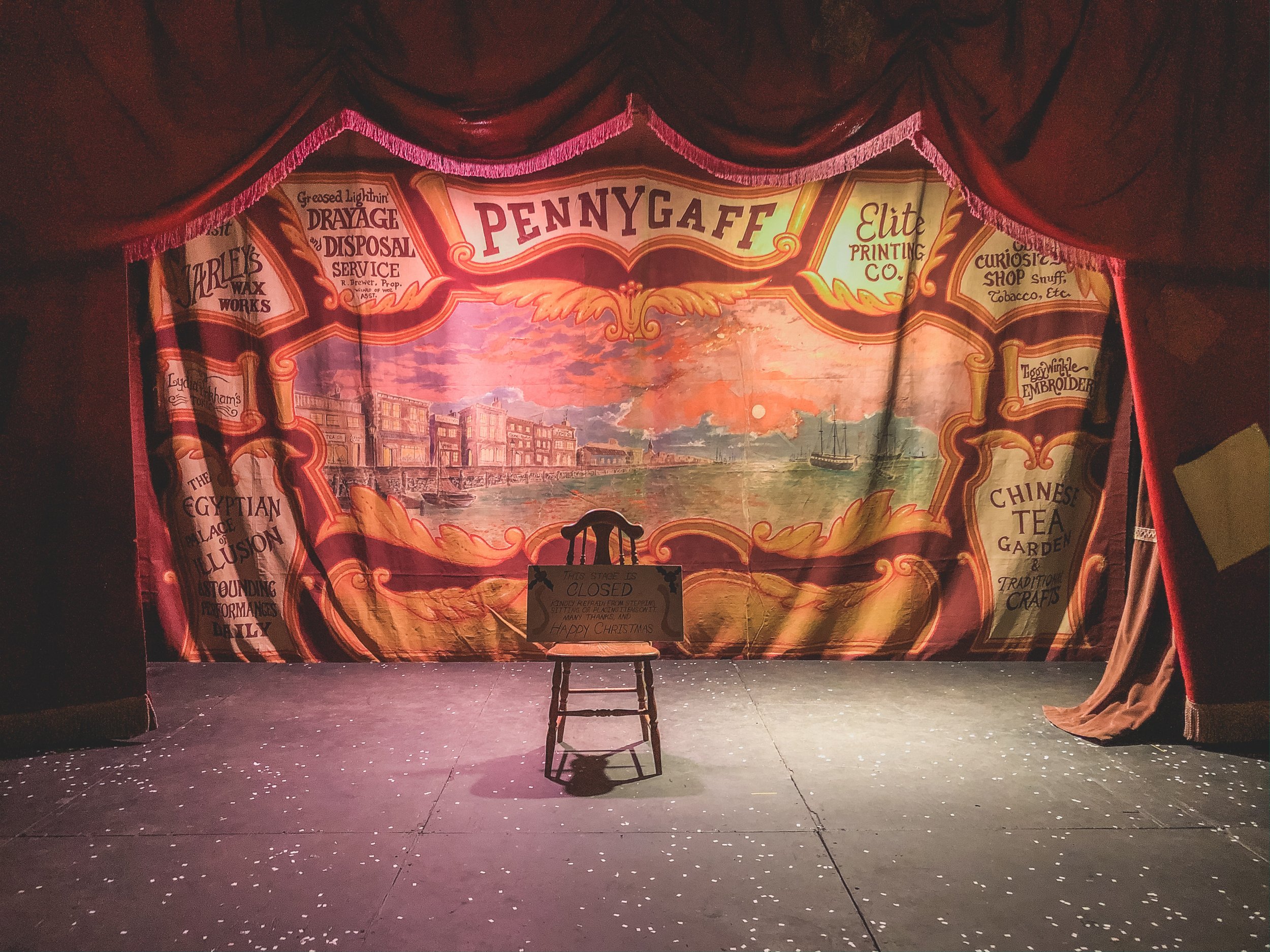

The old man raised his red eyelids, gnarled as a turkey’s. One finger – a finger as thin as the twigs they use to light the fire – emerged from beneath the poncho and pointed toward the palace of the Alvarado family, the only palace in that heap of clotted mud that is the village of Oquedal: a baroque façade that seems to have happened there by mistake, like a piece of scenery in an abandoned theatre.

One way of looking at If on a winter’s night a traveller is that a novel and ten short stories are offered in just 254 pages, and for good measure You fall in love. Calvino manages this compendious feat through an imaginative structure which he shared with a friend at the beginning of 1978, while he was writing the novel:

… the protagonist is the reader, addressed in the second person, and the reader is trying to read a novel which enthuses him but his reading is always interrupted for some reason or another and when he goes back to his reading he finds another novel which engages him even more, and the book contains N beginnings of novels (maybe 12 or 10) representing so many types of novel styles or rather ways in which novels are read. It will also include reflections on reading... [1]

It might all seem elliptically, didactically, opaquely, self-referentially postmodernist – rattling around the empty caverns of Theory. It isn’t any of that. You know from get-go that the novel is about reading and writing stories. You become more familiar with Yourself as the attentive Reader (though You may be surprised by what you haven’t previously noticed about who You are). If on a winter’s night a traveller is abundantly funny and ironic. There is no dreary postmodernist navel-gazing. Indeed, he cautions us about linking celebrity, wisdom and authorship with reference to ‘that anachronistic personage, the bearer of messages, the director of consciences, the giver of lectures to cultural bodies.’ [2]

The fun is everywhere. If on a winter’s night a traveller takes You to the university with Ludmilla. (It is Ludmilla, a student at the university, with whom you have fallen in love). Together you intend to consult scholars about the provenance of what You are reading. Instead of the generously open-minded, intelligent space You anticipated, You find Yourself harried in the corridors, crimped into a mean academic rabbit warren. You witness a take-no-prisoners argument, that no one can win, about who has cultural rights over the work of fiction You are reading (or trying to read). In a corridor Ludmilla chances across a fellow student, Lotaria, with whom she opens discussion on one of the novels You and Ludmilla started to read. Ludmilla is delighted to learn that Lotaria has also come upon the very same work. ‘Leaning from the steep slope,’ Ludmilla enthuses on page 71 , ‘the unfinished novel of Ukko Ahti, the Cimmerian writer!’ Lotaria perfunctorily demurs from Ludmilla’s attribution of authorship.

‘You are misinformed, Ludmilla. That is the novel, but it isn’t unfinished, and it isn’t written in Cimmerian but in Cimbrian; the title was later changed to Without fear of wind or vertigo, and the author signed it with a different pseudonym, Vorts Viljandi.’

‘It’s a fake!’ Professor Uzzi-Tuzii cries. ‘It’s a well-known case of forgery! The material is apocryphal, disseminated by the Cimbrian nationalists during the anti-Cimmerian propaganda campaign at the end of the First World War!’

Calvino does not try to fix this political mess of his own creation. He seems unfazed by obstacles to resolving authorial messes. On the inside of If on a winter’s night a traveller, an author (speaking on Calvino’s playful behalf) advises leaving messes for later:

If I think I must write one book, all the problems of how this book should be and how it should not be block me and keep me from going forward. If, on the contrary, I think I am writing a whole library, I feel suddenly lightened: I know that whatever I write will be integrated, contradicted, balanced, amplified, buried by the hundreds of volumes that remain for me to write. (p. 177)

You might perhaps write ten stories and a novel at the same time.

Book keepers are among the personas of readers played with during If on a winter’s night a traveller. Consider the bloodrush some readers feel when they cross into shelfed aisles via a bookshop door. While browsing therein, blood is surreptitiously let by the sucking truth that they must not buy another book. Calvino reminds them, reminds us all, in declarative capital letters that already on the shelves at home slumber ‘the Books Read Long Ago Which It’s Now Time To Reread and The Books You’ve Always Pretended To Have Read And Now It’s Time to Really Sit Down And Read Them’ (p.6).

I recognise the sadness that saps Mr Cavedagna, a long-suffering editor whom Mr Calvino arranges for Ludmilla and You to meet. Mr Cavedagna works at the publishing house where the star-crossed readers go in an attempt to defuse their exasperations with the disconnected parade of books they have started, at Mr Calvino’s invitation, but cannot finish, due to Mr Calvino’s distractions. Mr Cavedagna reminds us about books we have long planned to read; but reading plans rely on plots that do not hold for a lifetime, or a long time, or even a month. ‘I keep thinking,’ says Mr Cavedagna,

that when I retire I’ll go back to my village and take up reading again, as before. Every now and then I set a book aside, I’ll read this when I retire, I tell myself, but then I think that it won’t be the same thing anymore. (p.94)

A book finished is never the book begun. Everything is liminal, in-between, known and unknown, seen and unforeseen. Alexander Lee offers a good insight into why Calvino wrote stories as he did. Lee suggests that after the Second World War (in which Calvino fought with the Italian Resistance, in the ranks of the Communist aligned Garibaldi Brigades), deep pessimism infected Italy’s literary and philosophy communities. For some, no words could cogently represent collective experience; a writer could enlist only personal, introverted experience. Some thought of language as all we have. Others thought language was meaningless, conveying nothing of the real world. In Lee’s eye, Calvino cast off the pessimism and

… came to feel that it was his duty to try bridging the gap, no matter how difficult or implausible it might be. The key, he realised, lay in the uncertainty — or rather, its ubiquity… he saw that the unreliability of our perceptions is what unites us — not the objects of our experiences. So, if his writing was to speak to his readers, he would have to take this uncertainty as his subject.[3]

Earlier I mentioned Calvino’s whimsical slight about linking celebrity, wisdom and authorship. I do not throw that caution to the night, but I am comfortable in asserting that Calvino is a mage on the page. He turns familiar ways of telling into the spell of If on a winter’s night a traveller. It is a joy to be his dear Reader during this fabulous writing and reading masterclass. He wastes no words. The fun starts with the novel’s first sentences:

You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveller. Relax. Concentrate. Dispel every other thought. Let the world around you fade.

Let the fun, the game, begin.

[1] From pp. 482-483 of Italo Calvino: Letters – 1941-85, edited by Michael Wood, translated by Martin McLaughlin, and published in 2013 by Princeton University Press. (Reading If on a winter’s night a traveller prompted me to find out more about Calvino. I rarely read authors’ biographies; I prefer their stories to their story. But Calvino beckoned me and I have since tracked down a fund of essays, lectures, and letters.)

[2] The literature machine, Italo Calvino, translated by Patrick Creagh, Vintage Classics, 1997, p. 16.

[3] Alexander Lee. 2023. ‘The infinite delight of Italo Calvino.’ Engelsberg Ideas.

Calvino’s novel was published in Italy in 1980 as Se una note d’inverno un viaggiatore.

In 1983 it graced English as If on a winter’s night a traveller.

In this post I refer to Penguin’s Everyman edition, translated by William Weaver.